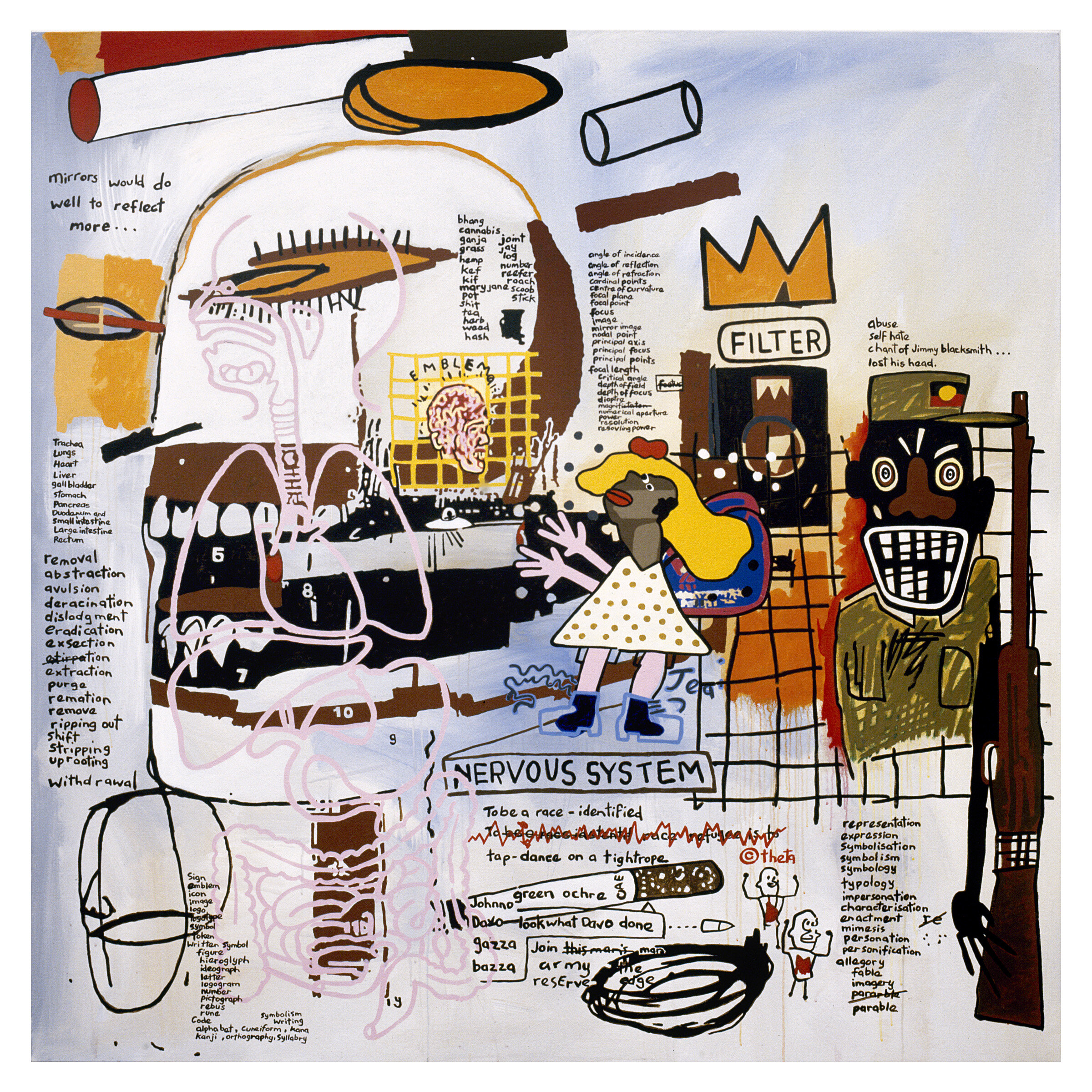

Gordon Bennett, Notes to Basquiat: Green Ochre, 2000, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, Private Collection, Sydney

This essay first appeared in the catalogue of the exhibition Gordon Bennett, curated by Kelly Gellatly at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 6 September 2007 to 16 January 2008.

Citizen in the making: The Art of Gordon Bennett

If I were to choose a single word to describe my art practice it would be the word question. If I were to choose a single word to describe my underlying drive it would be freedom. This should not be regarded as an heroic proclamation. Freedom is a practice. It is a way of thinking in other ways to those we have become accustomed to. Freedom is never assured by the laws and institutions that are intended to guarantee it. To be free is to be able to question the way power is exercised, disputing claims to domination. Such questioning involves our ‘ethos’, our ways of being, or becoming who we are. To be free we must be able to question the ways our own history defines us. [1]

After working for almost half his life in various trades, Gordon Bennett’s decision, at age thirty, to enrol as a full-time student at Brisbane’s Queensland College of Art, signalled a desire and determination to consciously change the course of his future.[2] Who was to know at this stage that in many ways this delay – described by Bennett as ‘a life crisis point’[3] – would occur at the right time, and that several factors – not least of all, the ‘young’ artist’s intelligence, maturity and talent – would combine to ensure his early success. Already well-read and particularly interested in psychology, Bennett’s exposure to and immersion in postmodernism and postcolonial theory at art school was to have a fundamental impact on the development of his practice. It is through these frameworks that he began to explore many of the complex issues that have remained central to his work in the twenty-year period marked by this exhibition.[4]

As an Indigenous Australian who had ‘a strictly Euro-Australian upbringing and education’ and who was unaware of his own indigeneity as a child,[5] Bennett’s early interrogations of the construction of personal and cultural identity, the power of language and the nature of representation not only coincided with but were also fuelled by the unfolding of Australia’s Bicentennial celebrations in 1988. This was a time when questions surrounding this country’s colonial history were similarly contested and debated. Given both the formal quality and intellectual content of Bennett’s early work, it’s not surprising that in this climate it was immediately included in prominent exhibitions (Bennett was curated into the prestigious Australian Perspecta exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney in 1989, just one year out of art school) and that critical acclaim swiftly followed his graduation. However, even during this first flush of success, the artist was mindful of the link between his identity as an Indigenous person, his choice of subject matter and the reception of his work: I think people knowing my Aboriginality does have a large bearing on how they read the work. I don’t know whether that’s fortunate or not. It’s just a fact of life that these things do have an effect … My quick success has something to do with my Aboriginality and that worries me. Let’s face it, Aboriginal work is flavour of the month.[6]

And this interest in ‘labelling’ or categorisation – and Bennett’s own position as an artist operating between Western artistic traditions and indigeneity – has continued to be an ongoing concern. Indeed as Susan Lowish has noted, with the benefit of hindsight it is possible to identify a number of themes within Bennett’s early paintings that remain of relevance to his current practice.[7]

The ability of Bennett’s oeuvre to fold back on itself while forging new ground – its interconnectedness, is just one of the many characteristics that ensure the continued significance of what is at times a confronting and expansive body of work. For during the twenty years encompassed by this exhibition, Gordon Bennett’s practice has systematically interrogated conventional representations and racial prescriptions for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australian peoples, with a particular focus on connections to place and nationhood, concepts of citizenship, and the articulation of histories alternate to the Anglo-European construction of Australia’s recent past. As such, Bennett’s investigation of the disenfranchisement of colonialism registers ‘a peculiarly Australian anxiety’[8] while resonating globally, and continues to issue an important contemporary challenge to both political conservatism and social complacency.

§

Painted in 1987 during Bennett’s second year of art school, The persistence of language and The coming of the light convey their difficult subject matter with a raw, accusatory intensity that is similarly embodied in their bold, expressionistic handling of paint and sombre, monochromatic palettes. Within these early works Bennett clearly foregrounds what was to become one of the most prescient concerns of his oeuvre – the role and effect of language on perception and understanding. This in turn raises questions around issues of ‘truth’ and our ability to interrogate (or indeed oppose) established cultural positions. As the artist has written: Language defines the invisible boundaries of limits to the understanding of the world of experience. It does not constitute a natural inventory of the world, but rather language is a system of conventional and arbitrary sounds and symbols that represent the subjective human perception of it. Thus a word does not represent an object in itself, it represents the image of the object reflected in the human mind.[9]

Bennett loosely chronicles the ‘progress’ of colonisation across the triptych format of The persistence of language – from the arrival of language (and education), figured by the threatening totemic heads mounted on ruler-like sticks, through religion, to the limp black figure hanging from a rope. The role of the viewer is clearly problematised through a shared position within the prison cell of the work’s third panel, where we are confronted by the scrawled and dripping blood-like taunts of boong, abo, darkie, koon … The upsetting and violent events that unfold across the painting are set against the oppressive backdrop of the suburbs, where Bennett lives. The inherent conservatism and sheer weight of the ‘sameness’ of suburbia is quite literally captured by the crush of buildings and the vacant gazes of its disembodied inhabitants, which press against the bars of the window of the cell.

By referencing the issue of black deaths in custody, this juxtaposition and its emphasis on the notion of insider/outsider, darkness and light, undoubtedly focuses on contemporary events while simultaneously questioning the very ‘foundations’ of Australian society.[10] For as Bennett revealed some years later in the ‘open letter’ that accompanied his work Home sweet home, 1993-4, it is in the suburbs that one is often confronted with the most insidious forms of racism: … I think it was the barbeques that got to me in the end. The party talk both at work and around the neighbourhood. The subject of Aborigines always came up. It was then that I felt an outsider. I could not fit in. The bloody boongs, the fucking coons, abo’s [sic], niggers – put them in a house and the first thing they do is burn it down. Try and imagine what it’s like, sitting quietly, listening to this shit while your stomach turns in knots – try to fit in, keep the peace, after all you live right next door, right? Who needs to be a target for all that bullshit – life’s tough enough as it is. So, there I sit, in a quiet rage, hoping no-one will notice my tan, my nose, my lips, my profile, because if I start trouble by disagreeing, then that would be typical of a damn coon wouldn’t it?[11]

While ironically referring to a Torres Strait Islander’s description of the arrival of the missionaries, The coming of the light foregrounds the Enlightenment values central to colonialism,[12] while simultaneously questioning the complex role of Christianity and specifically its impact on Indigenous societies. By appropriating the text-based 1959 Elias series of paintings by New Zealand artist Colin McCahon, Bennett uses McCahon’s own contemplation of the concept of doubt in these works (‘Will he come/let be/let be/will Elias come to save him’) to effectively ‘cast light’ on the desire of Australia’s European colonisers to supplant Indigenous belief systems with Christianity, their own model. But as this telling work conveys, the arm that brought knowledge or ‘enlightenment’ simultaneously threatens the Indigenous subject, thus amounting to a Judas-like betrayal.[13] Yanked from one of the building blocks of language, Bennett’s aboriginal jack-in-the-box (with all its connotations of entertainment and performance) stares in his last moments at a mirror that reflects not only his face, but the racist taunts formed from the most elemental components of the English language – our ABCs.

In 1988, the year of Australia’s Bicentenary, Gordon Bennett produced Outsider, one of the most hard-hitting and iconic paintings of his early career. Here Bennett deliberately evokes clichéd but long-held notions of ‘the tortured artist’ and connections between artistic ‘genius’ and madness by siting this horrific depiction of a decapitated Indigenous man within Vincent van Gogh’s Vincent’s Bedroom in Arles, 1888. Bennett places himself, as creator, within these questionable parameters, and uses this position and elements of ‘the grotesque’ to point to the violence at the heart of Australia’s ‘settler’ history and the related denial and deliberate effacement of Indigenous culture.[14] The binary opposition of insider/outsider suggested by the painting’s title – and its conflation of the positions of van Gogh, Indigenous Australians and Bennett himself as outsiders – is further reinforced by the tension between the evocation of van Gogh’s painting Starry night, 1889, at the top of the canvas (which in itself recalls Western Desert dot painting) and the heads of classical statuary that loll on the bed in the foreground of the work. Outsider similarly reflects the fear of the ‘Other’ and its violent fulfilment as it is played out in Australian author Thomas Keneally’s novel The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith and its filmic adaptation by director Fred Schepisi.[15]

At this stage of his career Bennett’s use of and connection with these sources was largely ‘empathetic’.[16] The works are charged with an energy and emotion that he later sought to deny through his shift away from the expressionist painting style that characterised his early work (also a conscious removal of his own gesture from the canvas) and his attempt to establish a critical distance between himself as ‘author’, his chosen subject matter, and his appropriation of the work of Australian and international artists for strategic and dialectical ends.[17] This endeavour would naturally take some time and was to grow in both its sophistication and complexity over a number of years. However, Gordon Bennett’s painting style almost immediately underwent a dramatic transformation, and during the late 1980s he returned to the sources of his own Eurocentric education, employing the graphic images of Australian school history texts to effectively fragment the telling and interpretation of this country’s founding stories.

In a painting such as Untitled, 1989, for example, the artist’s juxtaposition of image and text highlights the powerful role of language in perception, understanding and the structure of popular belief systems, when each image is naturally ‘read’ as an illustration of the text it accompanies. As the artist has noted and fulfilled in this work, the learnt structures of the English language can in effect be turned upon themselves to achieve a different end: It is interesting to note that many English words with a dis- prefix mean to reverse, undo, or subject to reversal, or undoing of the meaning of the word to which it is prefixed. It can thus refer to negation, opposition, seperation [sic], or deprivation. A conceptual relationship is therefore established between the method and the intention.[18]

Yet within Bennett’s constructed narrative grid, the work’s final panel – ‘dismiss’ – a Malevich-like black square, functions quite differently and is, in effect, an abstract painting in which, ‘Aboriginality has not evaporated, but is repressed … an absence heavy with the residue of metaphysical presence; black as presence, not absence’. [19] This final square defies the erasure that it pictures.

Terra nullius, 1989, employs a similar strategy of opposition by juxtaposing the instantly recognisable image of Captain Cook claiming Australia for the British crown (so burnt as it is, through the proliferation of historical images, on both our retina and minds that we actually feel that this is what the event looked like) with the physical realities of the subjugation of the original inhabitants of this supposedly ‘empty’ land. Shadowy indigenous figures appear in the background of Cook’s landing and seem to float upon the grid of the Union Jack, which presages both the mapping of country and its people that was to subsequently occur, and the way in which these European systems of representation effectively ensured the categorisation and control of Australia’s original inhabitants. Painted in a manner that replicates dot painting of the Western Desert, as well as the dot screen of photo-mechanical reproduction,[20] this sense of dispossession is further heightened by the roundel blazing sun-like at the top of the canvas and the accompanying footprints that not only mark former occupation but appear, in this context, to track attempts at escape. This motif is also used as a device to link the three components of Bennett’s ambitious Triptych: Requiem, Of grandeur, Empire, 1989. This work employs historical and personal imagery in combination within the form of the altarpiece, to convey a sense of mourning and loss; elegiacly reflecting on the complex relationship between colonialism and Christianity, its role as ‘civilising’ force, and the subsequent development of Australia’s mission culture.[21]

After an incident in 1989 concerning Bennett’s appropriation of a Mimi spirit figure by Maningrida artist Crusoe Kuningbal,[22] in his painting Perpetual motion machine, 1987, his investigation of the ongoing legacy of Australia’s colonial past was no longer established by the use of identifiable and culturally-specific Indigenous forms. Bennett unintentionally (and some would charge ignorantly) caused offence, for which he later apologised. However his use of Kuningbal’s design nevertheless highlights the complexities inherent in Bennett’s own desire at this time to come to terms with his Aboriginal identity, and to investigate his nether-position as an Indigenous Australian who was raised and educated otherwise.[23]

While Bennett did not entirely relinquish the use of dot painting in his work given its important signification of a very general notion of ‘Aboriginal art’, in his forthcoming series Notes on perception, 1989, he was to expand and refine the dialogue surrounding this aspect of his practice, while also reinforcing his broader intentions in continuing to use this motif. Works in this series were first commenced with gestural brushstrokes, followed by the insertion of dots in the spaces between these formative marks. By almost dissolving before one’s eyes at close range, and in effect, totally obscuring the image, these paintings – which depicted iconic imagery from the stories of Australia’s explorer history (Captain Cook, sailing ships and the like), as well as stereotypical images of ‘primitive’ Aboriginal subjects in ‘noble savage’ guise – quite literally played with ‘notions of perception’.[24] In having to step back in order to make ‘sense’ of these pictures, Bennett used the viewer’s active participation to emphasise that construction of the image by the mind (and not the eye) is in fact ‘based on the past learnt experience of cultural conditioning and culturally relative knowledge’.[25] As he explained: My use of dots, apart from their aesthetic potential, is in one aspect a reference to the unifying dot matrix of photographic reproduction and in another sense it is Aboriginal referential in the dots relationship to the unifying space between cultural sites of identification in a landscape that is not experienced as separate from the individual, but as an artefact of intellect. In traditional Aboriginal thought there is no nature without culture, just as there is no contrast either of a domesticated landscape with wilderness, or of an interior scene with an expansive ‘outside’ beyond four walls.(1) This notion led me to conceive of the Eurocentric perceptual grid, with its sites of iconographical signification, as a landscape of the mind – a ‘psychotopographical’(2) map where sites, located in memory, represent the subjective human identification with the perceptual world.[26]

The critical intentions of Gordon Bennett’s quotation of Australian artist Imants Tillers’ work in his Moët & Chandon Prize [27] -winning painting The nine ricochets (Fall down black fella, jump up white fella), 1990, were undoubtedly heightened by the artist’s recent negotiation, on a personal level, of the cultural, moral and ethical dilemmas embedded within the practice of appropriation. But the prestigious and high profile nature of the Prize was to similarly ensure that these issues were subsequently played out in the broader public arena.

In this complex painting, largely depicting dead Indigenous subjects, which in itself is a cropped version of an historical image derived from a contemporary source,[28] Bennett has embedded his own ‘take’ on Imants Tillers’ painting Pataphysical man, 1984 (executed in Tillers’ signature canvas board system). He is also referring, through the works’ title, to Tillers’ The nine shots, 1985, which appropriated German artist Georg Baselitz’s painting Forward wind, 1966, and significantly for Bennett the work of Indigenous artist Michael Nelson Tjakamarra (Five dreamings, 1982).[29] Within and beyond the context of postmodernism, Imants Tillers’ challenge, through appropriation, to issues such as authorship and originality (the artist’s immediately identifiable works are entirely constructed of other artists’ images), and his conscious ‘flattening’ of the images he works with (which are drawn from a variety of contexts and sources), raises undeniably difficult questions about the cultural specificity and meaning of images and the moral rights of the artist. However, the nine bleeding roundels (both cultural sites, targets, bullet holes and wounds) in The nine ricochets leave us in no doubt as to Gordon Bennett’s interpretation of Tillers’ use of Indigenous art at this time. A direct correlation is established in this work between the events of the violent backdrop, Imants Tillers’ work, and the appropriative practice that its presence signals. As Terry Smith has commented, Bennett wants to show that, when anyone takes pot shots, there are repercussions.[30]

Yet Bennett is entirely aware that he and The nine richochets are participants in and function as part of the very system of representation he aims to critique. While this circularity is embodied in his own strategies of appropriation in this work, it is perhaps most poignantly figured by the impossible three-pronged object in the red square (a nod to Malevich) that floats across his and, by extension, Imants Tillers’ work. The simple visual trickery that brings this object into view makes palpable the slippage between sight and understanding, and similarly highlights the constructed and indeed, learnt nature of belief and knowledge: Unlike the straight shots travelling directly to their vanishing points, ricochets map a curved dangerous space – here the paths of this ricocheting space being traced by the all-over drip technique of Jackson Pollock. Appropriation, Bennett seems to be saying, is uncanny. To begin with, the original is liable to ricochet back onto the appropriator. Despite the absence of origin instituted by the simulacrum, this origin is not easily foreclosed. Instead there is always an unaccounted surplus, as if the original shadows or haunts the appropriation. At the heart of appropriation is a conundrum …[31]

The cultural aspect of these constructs remains central to Gordon Bennett’s practice. And for these reasons, among many, he continued to engage with Tillers’ work in ensuing years.[32] In The recentred self, 1994, for example, an appropriation of Tillers’ The decentred self, 1985, Bennett consciously foregrounds, through the shift in the work’s title, the type of binary oppositions (such as insider/outsider) on which concepts of difference are established. In effect the painting is both claiming and obscuring the differences between each of the artists in bringing their work together. He also quite literally ‘colours’ Tillers’ painting with the celebratory and defiant hues of the Aboriginal flag. [33] However, despite the possibility of redemption signalled by the artist’s hovering black angel, the pain of history, and specifically black history, cannot be so easily erased. Paint runs blood-like down the surface of the work, red hand prints (recalling Outsider) pattern its lower region, and the image is painted over a skein of Pollock-like drips that lurk below the black ground of the canvas like healed scars or whip marks.[34] The distance between past events and present realities also collapse in the red welts that glow like fresh wounds, seeming to mark time or count down the days of a sentence. As Ian McLean has noted: The redemption Bennett reaches for is clouded with irony. But it is an irony which, for Bennett, is the sign of subjecthood; the irony of a subject divided against itself. [35]

§

Bennett first began appropriating the celebrated drip technique of American Abstract Expressionist Jackson Pollock in 1990. [36] He used his own replication of this performative technique to effectively interrogate the myth of the western artist as ‘hero’ (given Pollock’s status in art history) while similarly highlighting, in the case of Pollock, the very ground on which such a reputation is built. For it is the influence of the sand painting of America’s Indigenous people on this aspect of Pollock’s practice that interests Bennett. The ritualistic and ceremonial elements of this practice strongly echo, for the artist, the ground painting of Indigenous Australian culture, and in turn refer more broadly to the ceremony or ritual of the act of painting itself. [37] In Poet and muse, 1991, Bennett depicts this aesthetic appropriation as a form of colonisation whose violence is clearly figured by the threatening presence of the stockman’s whip, which is subsequently multiplied by the threads of paint that dance across the surface of the work. Yet, as Ian McLean has noted, the drip technique similarly allows Bennett to picture an alternative to the perspectival space of colonialism;[38] a system the artist quite literally ‘outed’ in the composition of previous and later works. While the cultural and spiritual differences between the two figures is clearly delineated in Poet and muse, Bennett also employs the open-endedness and visual possibilities of Pollock’s web of drips (one’s ability to ‘see’, like cloud-gazing, images embedded within them) to refer to the manner in which myths or histories provide a sense continuity for particular cultures, and together combine to form a complex matrix that in effect comes to function as a world view: [39] … the black figure stoops with hand extended, dipping into the fluid matrix of the river, as if reaching for the ‘target’ as symbol for cultural site, ie. a focus for meaning to life – a culturally relative identification with the site of the river. One may say that the river with its swirling constant flow – the chaos of the world as referred to by the underpainting – is a metaphor for life; we are swept along with it clinging to our sense of identity and of self, as understood and constructed by history, in an effort to stay afloat. [40]

In Myth of the Western man (White man’s burden), 1992, the drips of Pollock’s seemingly chaotic and ‘unconscious’ technique spin around the canvas, throwing up dates that mark significant (and largely untold) events in Australia’s history, ending in 1992, the year of Mabo [41] and of the painting’s execution. In drawing on an image from a primary school text illustrating an episode from the Burke and Wills expedition, [42] Bennett points to the relationship between notions of ‘progress’ and the western concept of a linear history, while also questioning, through the specific event that he pictures, the type of stories that are celebrated as part of this country’s colonisation. Set against the ‘heroics’ of the grand Australian explorer narrative that serves as the loci of the painting, the dates on the blue flags that swirl across the composition similarly signal the real costs that underlie many of the historic events valorised as part of Australia’s development as a nation. [43] A more recent sense of this ‘development’ is also signalled by the ‘blue pole’ at the centre of the image, which signifies Australia’s entrance into modernity through the controversial acquisition of Jackson Pollock’s Blue poles, number 11, 1952, by the Australian National Gallery, Canberra during the Whitlam era. [44]

During the period in which Gordon Bennett was communing with Pollock – for as Jill Bennett has identified, the artist displays a tendency to ‘feel into’ the images he quotes while similarly ‘speaking through’ the artists he appropriates [45] – he also began to develop a body of work that incorporated the mirror, a tool metaphorically and physically entwined with an investigation of self and one that offers a space of possible transformation. As Ian McLean has commented: If the mirror is where we inspect ourselves, the inspection is not a passive survey of the self, but a dynamic means to reconstruct and imagine ourselves differently. Before the mirror we make ourselves up. Hence the mirror is a metaphor for an imaginary liminal space in which, as Alice discovered, anything is possible, the former boundaries and limits of things dissolve, and even the grotesque appears normal. Because the mirror image is a reversed figure, it is also often conceived as a doorway to another inverted fantastic world, an antipodes, the realm of the ‘Other’. Bennett put a mirror (rather than a microscope) to Australia, thus picturing a narcissistic historiography. For him the reflective surface of the mirror not only upturns (inverts) the real world of colonialism, but is an icon of the corrosive threshold between the coloniser and colonised, a liminal zone where the discourses of colonialism are exceeded, the past and future re-negotiated, and history re-written. [46]

The mirror was a central device in Bennett’s early painting The coming of the light, 1987. Here the artist incorporated a version of the mirror he used for shaving [47] (thus adding an inflection of self-portraiture to the work) and it similarly appears, in the guise of an appropriation of the work of American Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein in Interior (Abstract mirror), 1991, floating across the canvas as a kind of counterpoint to the perspectival grid that both frames and constrains the group of Indigenous subjects pictured at its centre. Through the reflection of the viewer that it offers, the mirror implicates and accuses the audience of the Eurocentric mind set and value system that the grid represents, while also alluding to a space in which different perspectives may be possible. As the artist has explained: Perspective may be seen as a symbolic reference to a certain human (European) teleological progression, or ‘evolution’, toward some ultimate consummation, (as represented by the central vanishing point – C.V.P.). The C.V.P., always invisible, just over the horizon, may be understood as that point which acts as a ‘site of identification’, ie. that which gives direction, depth and continuity to European culture – toward the ultimate conclusion of history or the arrival of the fully evolved state of humanity. But, all this is of course is culturally relative. [48]

However, it is the monumental Painting for a new republic (the inland sea), 1994, which encapsulates the significance of the mirror to Gordon Bennett’s practice during this period. This developed into a series of Mirror works produced by the artist between 1994 and 1995. If the mirror, as Ian McLean has noted, is emblematic of ‘the narcissistic regime of colonialism’ for Bennett, [49] in Painting for a new republic the artist inserts and asserts the presence of the ‘other’ denied by this position by placing the opposing world views and historic realities of the coloniser and colonised on the left and right side of his canvas. Through their position at the top of the work, the mirror forms assume an important symbolic role, straddling the gulf between the activities of European explorers and the human costs of colonisation figured at the left of the work, and the radiating circles of what appear to be a Western Desert painting at its right.

The mirror allows these different positions to reflect back on themselves (which is literally figured by the blurring of both ‘perspectives’ at various junctures across the canvas), offering a space of deconstruction [50] that proffers the possibility of the (re)construction, or at least imagining, of something new. Like the mirrors contained in the boxes of Bennett’s installations The aboriginalist (Identity of negation: Flotsam), 1994, and If Banjo Patterson was black, 1995, the mirror also implicates the viewer (by reflecting back our own visage) while raising questions about personal identity and agency. This has a particular relevance to Gordon Bennett’s own position as a person of Indigenous and non-Indigenous descent [51] and informs the investigation of identity politics and the genre of self-portraiture that runs through the artist’s entire oeuvre. As Ian McLean has noted: the mirror is a central element in the reconciliation that he seeks between the self and its others. [52]

§

In his Self portrait (But I always wanted to be one of the good guys), 1990, Bennett uses the conflict at the heart of his own socialisation (raised and educated as a white child while unknowingly black – ‘I AM LIGHT I AM DARK’) and hence the inherited ‘perspectives’ of his education as such, to problematise issues surrounding the construction of identity and perceptions of self. The sense of opposition between black and white, darkness and light and bad and good established in the work is also embodied by the figure of the artist drawn from a family photograph of him dressed as a ‘cowboy’. Set in contrast to the Aboriginal people who are consequently cast as ‘Indians’, Bennett’s role as playtime hero necessarily disguises the realities of colonisation and racial oppression at the core of such Hollywood-style narratives. Framed within the ‘I’ of Colin McCahon’s declarative ‘I AM’ from his painting Victory over death 2, 1970, Bennett’s presence suggests that the assured and relatively straightforward sense of self of his childhood will always ellude the postcolonial subject. [53]

Since his days as a student, Gordon Bennett has experimented widely within the realms of traditional self-portraiture by incorporating his own face within his work. Most recently this has taken the form of a large series of photographs. Here we witness the artist at play, using the computer as a tool of transformation to wildly distort his face and variously overlay it with patterns and lurid colour. [54] However, as Bennett’s own obliteration of self in his Requiem for a self-portrait, 1988, testifies (a work in which he painted out a self-portrait with a layer of black paint)[55] he has always maintained a healthy scepticism of simple investigations of the self that remain divorced from the broader conditioning forces of history and culture. Thus within the examples of self-portraiture that thread through Bennett’s oeuvre, there emerges a more subtle and abstracted engagement with this genre; and one from which the artist’s likeness is entirely absent.

The sense of ‘knowing’ oneself (via family), or of certainty, which is evoked by the use of everyday domestic objects in Bennett's Self portrait (Ancestor figures), 1992, is immediately undercut by the presence of his Constructivist-style drawings and black angels (harbingers of good or evil?) embedded within the installation’s altar-like display. The combination of past and present, figurative and abstract within this work, deliberately defies closure, and while the coloured light emerging from the half-opened drawers of ‘history’ and ‘culture’ seems to offer clues to the ‘individual’ enigmatically displayed before us, we are provided with no answers. We are, however, left in no doubt about the competing forces attributable to the construction of self, and as Bennett literally figures in the half-mirror form of Self portrait (Schism), 1992, the very real personal and psychological costs that can arise if the specific nature of one’s cultural conditioning is unable to be questioned and effectively reconciled. As the artist explained during this period: I was socialised to believe that the [Eurocentric] ‘I’ … included me, totally. When I discovered my Aboriginal descent I first denied it and repressed it. When the repression became unbearable, and that was a true decentring, not a matter of ‘failed locality’ [Tillers] but almost of my entire system of belief – I mean psychic rupturing. [56]

In the Malevich-style cross paintings of Self portrait (Schism), [57] this ‘rupturing’ is rendered physically by the texts incised into the works’ surface like wounds; litanies that reveal a conflicted position of defiance and resignation. [58]

Bennett’s Self portrait: Interior/exterior, 1992, similarly makes palpable the physical and psychological costs of racism by overlaying the bodily and psychic markers of its effects on coffin-like forms that mirror the height and shoulder dimensions of the artist. Within a space demarcated by the controlling presence of the whip, this work speaks of the history and repetition of violence at the heart of racism while most poignantly evoking, through the possibility of self-harm threatened by the work’s text, ‘the wounding of the human spirit’: [59] It may be argued that in taking this position I am portraying black people as victims. This was indeed my intention and I wanted to not only ‘play the victim’ but to take it further and use that energy to advantage by not resisting, or trying to display strength, but to show pain and how much it hurts, even to the extent of self-mutilation. In this I am drawing on Aboriginal funeral ceremonies in which ritualised public displays of grief and mourning can involve blood letting and cutting one’s own body. Lucio Fontana’s cut canvases and the ceremonial scarification of initiation rights common to both Aboriginal, and some African peoples, were both factors in making these works. My interest in Taoism is also significant in the sense of utilising a strategy of least resistance, which uses an aggressor’s energy by turning it to one’s own advantage, rather than opposing a force directly, better to intercept obliquely, or roll with it turning the opposing energy around for your own advantage. [60]

By the mid-1990s, Gordon Bennett came to feel he was in an untenable position. While his work was increasingly exhibited within a national and international context, the combination of his position (or as Bennett would argue, ‘label’) as an (urban) Aboriginal artist, and the subject matter of his work, seemed to ensure inclusion within certain curatorial and critical frameworks, and largely determine interpretation and reception. It is undeniable that many of the issues raised by Bennett’s practice are deeply connected to the artist’s personal experience, circumstance and sense of self, and that the content of much of his work has drawn upon his struggle to come to terms with his indigeneity (‘I wanted to explore “Aboriginality”, if only to heal myself …’). [61] Yet cultural and social structures surrounding perception, representation and identity that Bennett aims to deconstruct in his work were ironically serving to pigeonhole him. As he has stated: I have never started out to do a ‘political’ painting. If my work is political then that is because of the politics of my position and the cultural climate in which I live and work. I didn’t go to art college to graduate as an ‘Aboriginal Artist’. I did want to explore my ‘Aboriginality’, however, and it is a subject of my work as much as colonialism and the narratives and language that frame it, and the language that has consistently framed me. Acutely aware of the frame, I graduated as a straight honours student of ‘fine art’ to find myself positioned and contained by the language of primitivism as an ‘Urban Aboriginal Artist’ … I have tried to avoid any simplistic critical containment or stylistic categorisation as an ‘Aboriginal’ artist producing ‘Aboriginal Art’, by consistently changing stylistic directions and by producing work that does not sit in the confines of ‘Aboriginal Art’ collections or definitions. At the same time I have resisted being a ‘spokesperson for my people’ – since I do not have, nor do I not seek, such a mandate – by declining to speak about my work. [62]

Bennett has since gone on to categorically refuse the inclusion of his work in ‘Aboriginal’ art exhibitions, preferring, as artists such as Tracey Moffatt have done before him, to be conceived as a ‘contemporary’ artist who just happens to be Indigenous and whose work encompasses an investigation of Aboriginality and the construction of identity within a broad range of complex and interconnected issues. But as the artist discusses in his interview with Bill Wright in this volume, escaping this kind of classification is not easy. This is where John Citizen, Bennett’s artistic alter ego, plays a role, allowing the artist to step outside of these strictures to create a body of work that exists in stark contrast to ‘signature Gordon Bennett’. It is not without certain irony that since his first exhibition at Sutton Gallery, Melbourne in 1995, Citizen has developed a strong exhibition history and is now represented by work in important public and private collections.

Yet from the beginning of John Citizen’s first forays into the art world, he has displayed a complex and at times perplexing relationship to the work of Gordon Bennett; variously collaborating with Bennett (as we witness in a group of works on paper from 1996), appropriating his imagery, and using it to decorate the magazine-style living rooms of his recent Interior series. Within their slabs of high-keyed decorator colour, meticulous arrangement of designer furniture, and paintings selected for aesthetics rather than content (the ‘that will look good over the couch’ approach), these rooms appear to endorse and promote consumption and material possession (as do the home magazines from which their images are drawn), while simultaneously critiquing, through their very ‘emptiness’, the vacuous desires at the heart of such ventures.

Read in this way, Citizen’s ‘coloured people’ are indeed the perfect occupants of his terrifying domiciles – all surface, colour and bonhomie as they ape a ‘good time’ for the camera. But this is to overlay a set of values on John Citizen’s practice that one can’t necessarily assume. These paintings are both a deeply cynical and darkly humorous exercise, and it is in the space created by the disturbing lack of ‘presence’ or engagement of this ‘everyman’ artist that we are left to ponder both his and Bennett’s motivation. Interestingly, the ‘[w]ithdrawal and concealment, and … absence that is close to invisibility’, noted by Zara Stanhope of these works, [63] is also a characteristic of Bennett’s recent body of abstract painting. These recent paintings provide, in a way different to his ‘being’ John Citizen, the kind of ‘freedom’ that Bennett has sought as an artist [64] – a release from being ‘Gordon Bennett’ and the weight and expectations surrounding his practice. As the artist expounded in 1999: Yes, I am using John Citizen increasingly. Some may see this as a clever appropriation of the Australian ‘every man’ but I see it more as a reappropriation of my self which has been othered to the point where I can’t identify with ‘Gordon Bennett’ the Aboriginal (life as an adjective is exasperating). [65]

§

In 1995 Gordon Bennett commenced Home décor, a body of work that developed into an extensive series over the following three years, marking a period of quite dramatic transformation in his practice. These works initially began as appropriations of the stylised ‘Aboriginal’ designs of Australian modernist Margaret Preston, who from the 1920s promoted the adaptation of indigenous motifs in interior decorating, and later incorporated Aboriginal art forms within her own work. [66] In his first series of works on paper, Home décor (after Margaret Preston), Bennett points to the contemporaneous cultural and social forces behind Preston’s use of Indigenous visual culture by quite literally ‘containing’ her designs behind the ‘civilising’ domestic structure of the white picket fence. While Preston’s well-intentioned nationalist sentiments and desire to develop a distinctly ‘Australian’ art were integrally linked to her use of and interest in indigenous forms, Bennett’s own dislocation of ‘her’ work highlights the artist’s effective claim (and corralling) of the ‘primitive other’ in her practice.

In his eventual incarnation of the Home décor series: Home décor (Preston + de Stijl = Citizen), Bennett pushes these connections to Preston even further by basing the ‘abstracted’ Indigenous figures in these paintings on the stereotypical (if not grotesque) representations of Aboriginal people from Preston’s late work. [67] While on one level this may be considered a direct criticism of Preston’s intentions and endeavour, Bennett’s own appropriation of the racist names and logos of Australian domestic products from this era in earlier work insightfully situates Preston’s project within a broader cultural malaise that fostered and encouraged the stereotypical representation of Aboriginal people during the early twentieth century. [68] Similarly, as Nicholas Thomas has commented, the ‘Home décor’ of the series’ title may refer to the domestication of Aboriginality (think of the kitsch representation of Aboriginal figures on ashtrays, tea towels, teacups and the like) and the ‘Aboriginalisation’ of the domestic space, but while the ‘Aboriginal emblem or painting is desired; the Aboriginal neighbour is not’. [69]

Like much of Gordon Bennett’s practice, the Home décor paintings replicate, defy and further complicate many of the oppositions (and hence, issues) initially suggested by the artist’s knowing juxtaposition of multifarious signs. For example, Bennett evokes the ‘pure’ colour and form of de Stijl abstraction and its expression of utopian ideals in these works, while also serving to undermine them. For the bodies of the Aboriginal figures which variously weave between, hang from, dance among and appear trapped behind the bars of colour that cross these canvases, purposefully reject the flatness of the abstract picture plane while also highlighting the historical context(s) against which such exalted ideas are played out. [70] These complexities become especially evident in a work such as Home décor (Preston + de Stijl = Citizen) Post-painterly realism of a peasant woman in two dimensions or Red square, 1997. The Aboriginal woman at the centre of the canvas stands in profile, replicating the poses of nineteenth century ethnographic photographs in which subjects were positioned against instruments that measured and recorded their height for the camera. While one of the bars of the grid that sections the work effectively echoes this colonial purpose, the woman appears both apart from, and somehow contained within, the different forms of representation figured in the painting. Yet because the work’s lattice-like grid seems to physically represent the Eurocentric structures of language and representation interrogated by Bennett throughout his oeuvre, the subject is also ‘read’ against the histories evoked by the Mondrian-like square that she carries – the artist’s incorporation of a Preston ‘Aboriginal’ design and the Malevich painting referenced by the work’s title and the red square that serves as its background. [71] Within the different dimensions created by this layering, Bennett effectively evokes the complexity of colonial history and its contemporary resonances within Australia and more broadly. As the artist has written: … De Stijl (the style) was based on a multidisciplinary approach that embraced all aspects of formal creation and aimed at universality. I am also interested in Mondrian’s theosophic concepts which led him to create an abstract visual language in order to represent the universal harmony that would result from the resolution of the antitheses between the masculine and feminine, the static and the dynamic, and the spiritual and the material. While such a resolution would be nice, I am more interested in the dynamic/static interplay between the binary opposites of abstract/figurative, black/white, good/bad, right/wrong, inclusion/exclusion to name a few. Here I am merely adding to Mondrian’s list some of the binaries that occupy me at present.

Within the modernist grid of Mondrian’s spiritualist universality and Preston’s stylistic utilitarianism, I hope to further explore a history of ideas, the history of events and spaces between the binary opposites that form their foundation, and which form our sense of ourselves. After all there must be some unity in exploring the common ground between self and other. [72]

In the ‘cut and paste’ aesthetic of the Home décor series we are also able to gauge the growing importance of the computer to Bennett during this period; a tool which enabled him to both experiment and successfully ‘build’ his compositions before physically undertaking their complex and time-consuming execution. [73] However, while Bennett’s sampling of images in these works has contemporary correlations in the music of hip hop and rap (which Bennett enjoys and has influenced later work), it is the strains of improvisatory jazz suggested by paintings such as Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie-Woogie, 1942–43, that seem to bounce across the gridded surface of these works.

In the artist’s Home décor (Preston + de Stijl = Citizen) Dance the boogieman blues, 1997, the coloured bars of Mondrian’s New York City, 1941–42, are in part transformed into a musical staff from which hangs the form of a quaver, grinning minstrel-like at a stylised Aboriginal figure who appears to dance along to the music he makes. Through this combination of stereotypical representations of the black American and Aborigine, Bennett draws a correlation between the history of racial relations in the northern hemisphere and the Australian situation; a correlation that was to build in significance for the artist in the coming years.

While the painting seems to equate the rapid adoption of black forms such as jazz by white society (and Mondrian himself is a perfect case in point) with Preston’s appropriations, the work’s title playfully suggests that these cross-cultural ‘dialogues’ (theft or homage?) fail to either disguise or correct the deeper cultural assumptions and divisions that lie at their core.

As Bennett’s Home décor project developed, the paintings in the series became far more complex in their layering, with the artist literally overlapping his appropriated images in a seemingly endless cycle of use and re-use. In monumental canvases such as Home décor (Preston + de Stijl = Citizen) Panorama, 1997 and Home décor (Algebra) Ocean, 1998, works from the artist’s usual grab bag of artistic sources (along with the inclusion of a new ‘participant’, like Basquiat), are cropped, obscured, and at times barely recognisable, and are increasingly seen alongside versions of Bennett’s earlier paintings. The artist’s use of PhotoShop is certainly a factor, [74] ensuring that the works’ jostling images and multiple, competing sources demand a different kind of viewing and interpretation. Nothing is settled here (the eye certainly can’t rest), and the deconstruction and investigation of binary opposites that had come to characterise Bennett’s prior work is now virtually impossible to detect. History is no longer solely interrogated through Bennett’s use of found images but is also conjured into the present by his earlier work. [75] As Ian McLean noted: Bennett has always sought a praxis by putting into play multiple rather than singular readings, forcing the viewers’ hands by demanding from them a further interpretation. All good art is performative in this sense. But Bennett’s work is performative in a strong sense in that this demand for interpretation is the actual subject of the art. The multiple texts of his art mobilise a field of ambiguity that the viewer must anxiously negotiate and navigate. With PhotoShop he found a way to ratchet up this anxiety by increasing the speed and density of the discursive traffic. [76]

§

In 1998 Gordon Bennett was invited to participate in a contemporary art fair at New York’s Gramercy Hotel. This invitation – and specifically the context of exhibiting in New York – was to provide the impetus for a new body of work that drew upon and paid homage to the idiosyncratic practice of American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat (who was the first contemporary African American to receive international art world acclaim), and in which the sampling of Bennett’s earlier Home décor series radically shifted gear. As Bennett declared in an ‘open letter’ to Basquiat, written ten years after the artist’s death, he hoped that his appropriation of Basquiat’s work would enable him to communicate via the ‘language of the New York context’, while also serving to highlight ‘the similarities and cross-connections of our shared experience as human beings living in separate worlds that each seek[s] to exclude, objectify and dehumanise the black body and person’. As he expanded: To some, writing a letter to a person posthumously may seem very tacky and an attempt to gain some kind of attention, even ‘steal’ your ‘crown’. That is not my intention, I have had my own experiences of being crowned in Australia, as an ‘Urban Aboriginal’ artist – underscored as that title is by racism and ‘primitivism’ – and I do not wear it well. My intention is in keeping with the integrity of my work in which appropriation and citation, sampling and remixing are an integral part, as are attempts to communicate a basic underlying humanity to the perception of ‘blackness’ in its philosophical and historical production within western cultural contexts. The works I have produced are ‘notes’, nothing more, to you and your work, posthumously yes, but importantly for me – living in the suburbs of Brisbane in the context of Australia and its colonial history, about as far away from New York as you can get – these are also notes to the people who knew you and your work, those who carry you with them in their memories and perhaps in their hearts. [77]

In the group of twenty-one works on paper that kick started the expansive Notes to Basquiat series, Bennett’s very different approach to the work of (and working with) Basquiat is immediately apparent, as is his relationship to Basquiat’s subject matter and the ‘story’ of the artist himself. Bennett’s Notes are no longer built upon the kind of appropriation that characterised his earlier practice and instead display a sophisticated mimicry of Basquiat’s raw street style. While these works certainly reference ‘signature’ Basquiat motifs, such as the childlike evocation of the crown and the artist’s use of lists and language (to name but a few), they now appear in works entirely of Basquiat’s ‘hand’ along with recognisably Australian symbols that are similarly woven within the compositions. As Jill Bennett has posited, Gordon Bennett may well be ‘smitten’ [78] with Basquiat, but this is not to infer in the case of the artist’s use of his practice, that ‘love is blind’. As she explains, Bennett is, in effect: … entering the interstitial meeting place that Basquiat opens up. In doing so, he does not simply imitate or act as Basquiat, nor does he insert himself into a frame or picture of Basquiat’s making. Combining with Basquiat is, for Bennett, a way of doing history and politics, and of examining the foundations of identity and experience. If Basquiat invents a certain painterly method, Bennett does not simply ‘borrow’ this in order to elaborate his own concerns. He is interested in how Basquiat’s work might be encountered from a different place, and in what happens when different accounts of history and experience are registered simultaneously within a given frame … [H]e explores the heightening of affect that occurs through combination, deriving a new form for his work out of an empathetic connection felt for another. [79]

The experience of race and life generally in the northern and southern hemispheres are differentiated, and in turn conflated, in these and later works. While the skeletal structure of the figure in Notes to Basquiat: (ab)Original, 1998, for example, speaks of commonalties and of a shared stereotyping of ‘blackness’ (which is also played out in the work’s unfolding text – ‘same but different / different but the same’), the news report recorded in Notes to Basquiat: True blue, 1998, reveals a quintessentially Australian context, in which there are, no doubt, global parallels. This sense of ‘same but different’ reverberates across these works and is similarly reflected in Bennett’s knowing relationship to Basquiat and his practice. Indeed, as a painting such as Notes to Basquiat: Green ochre, 2000, demonstrates, as the artist’s use of and familiarity with Basquiat’s ‘language’ develops, it becomes increasingly difficult (and almost unnecessary) to determine where Basquiat leaves off and Bennett takes over.

Gordon Bennett further develops his relationship to music in the Notes to Basquiat series by replicating the much admired sampling and raw spoken lyrics of rap and hip hop (favourites include 50cent, NWA [Niggaz with Attitude], Eminem and the Fun Loving Criminals) [80] in his execution of these complex works. While Basquiat’s passion for jazz – as the frequent references to Charlie ‘Bird’ Parker in his work attest [81] – is often seen to influence the particular musical ‘feel’ or ‘rhythm’ of his canvases, it is no coincidence that rap and hip hop emerged from the streets of his home of New York City during the early 1980s (Basquiat was for a time also in a rap band) and it is to the syncopated lyrics of these contemporary genres that Bennett re-mixes his work. The testosterone-fuelled aggression of these forms is similarly reflected in the pumped-up masculinity of the Notes to Basquiat series, heightened through the works’ successful combination of rapidly executed form and jarring juxtaposition of areas of flat, bold colour. As the artist has stated: In the computer details images are cut up and rearranged as are music samples using different software. The samples becoming something new with references to the past but in the here and now. It’s like something we’ve heard/seen before but not quite, it turns memory into a new experience with the present and with that new possibilities for the future. [82]

Even when Bennett re-samples Bennett in these paintings – as he does repeatedly through the use of the perspectival grid, such motifs are often no longer recognisably his, but are instead translated into (or seen through) Basquiat’s immediate, calligraphic style. But as suggested by the rap-like banter (‘angle of incidence / angle of reflection / cardinal points / centre of curvature …’) that runs between the black and white heads in Notes to Basquiat: Double vision, 2000, the perception of the black subject (and artist – whether Bennett or Basquiat) remains essentially the same, and is integrally connected to issues of perspective and framing (and education and knowledge).

The inclusion of lines of text in the Notes to Basquiat series – written out like the ‘lines’ that serve as punishment for a naughty school child [83] – plays a particularly important role, and together with the musical inflection of these works encourage an active participation of the viewer and a kind of ‘performative’ engagement. As these words roll off the tongue or scroll through the mind, the subtle shifts in meaning and allusion created by Bennett’s thesaurus-inspired word-play activate the complex web connecting sight, speech and thought in a way that reflects the links between history and meaning established in his oeuvre. Yet the Notes to Basquiat series is deliberately inconclusive, and seems to revel in the possibilities opened up by re-use and re-cycling, and its embodiment of ‘a process being kept in play’. As Bennett has commented: The inclusion of text in the paintings reads something like spoken word lyrics or poetry. Any viewer of the work will no doubt be drawn to recite the text in their mind (as they read it) so the work acts to enter the viewer something like a song can ‘stick in the mind’ or a poem can create an image in one’s mind. Poetry doesn’t seek closure on its meaning. I think it seeks to go beyond the words on the paper into a world of metaphor, allegory, images and ideas in order to say ‘something’ that may not be said with just words. [84]

In the aftermath of the devastating events of September 11, 2001, Gordon Bennett produced a group of paintings from the Notes to Basquiat series that responded directly to this dramatic and somewhat surreal event. These works are located within the transformed landscape of New York City after the attacks, and are the first within the series to depict an identifiable place; Basquiat’s home. But while Basquiat’s graffiti-style work decorated these streets and his meteoric career in many ways encapsulates the possibilities of New York during the early 1980s, the dramatic ‘homecoming’ figured in these paintings depicts a place that the artist could not know. [85] However, through Bennett’s imagined relationship with Basquiat – one of shared identity politics and experience, he is able to use the artist’s vocabulary (and its local inflection) to speak of the confusion, pain and trauma of this event, while similarly prefiguring the global resonances that were to follow.

The competing elements within the 9 11 paintings seem to push and jostle at the surface of the canvas in crowded and intense combinations of shape and colour. Within this new context, Basquiat’s childlike drawing of a plane is now a threatening presence, [86] which is joined by a proliferation of other planes (or potential missiles) whose flight paths cross these already chaotic skies. Schematically outlined skyscrapers lean at terrifying angles and are somehow pictured at a moment just prior to impact, which also evokes their eventual collapse. Indeed, this sense of foreboding and tension, of being positioned at a pivotal moment of unknowable and potentially dramatic consequence, pervades the entire series. And as the time registered on the video recorder in the painting Notes to Basquiat (CNN), 2001, so poignantly highlights, thanks to the immediacy of contemporary communications technology, geographic distance from the attacks on the World Trade Center in no way determined a certain level of emotional (and/or political) response. While this tragedy was enacted on a very specific place, it was nevertheless felt and experienced globally. As Jill Bennett has noted: If the trauma of 9/11 was geographically centred on the United States, it clearly was not contained within national boundaries. The immediate shock of 9/11 was felt viscerally across the globe – even though it may not have been experienced identically by citizens of New York City, London, and Pakistan; but, by the same token, the nature of one’s affective or empathetic response was not necessarily a function of belonging to a nation. There were bereaved families in Asia and Europe, for example, who were more traumatized than many Americans who weren’t directly affected by the tragedy; and there are asylum seekers in Australian detention centers who might be regarded as suffering greater hardship than the average U.S. citizen as a direct result of the events of September 11. [87]

Jill Bennett continues to emphasise however, that this sense of the global impact of 9/11 was later overshadowed by the highly charged nationalist sentiments that served as the backdrop for the US-led ‘war on terror’; [88] a subject that Gordon Bennett also briefly engages with in his later Camouflage series.

The bold, seemingly abstract patterns that decorate and fill the skies in the 9 11 works are a version of the Arabic Shamsa (literally, sun); a form which is often used to adorn the inside covers of the Holy Koran. In Notes to Basquiat (The coming of the light), 2001, this riffing between sun, light, illumination and knowledge is literally figured by the juxtaposition of the torch from Bennett’s earlier painting, which introduces the works’ connotations of colonialism and racism, while echoing within this particularly American context, the heroic stance of the Statue of Liberty. [89] Australia is also immediately evoked (or implicated?) by Bennett’s inclusion of Pollock’s Blue Poles in Notes to Basquiat (Jackson Pollock and his other), 2001. This work’s prominent ‘pole’ forms seem to replicate the crumbling ruins of the buildings at Ground Zero, while also signifying the strength of our shared (colonial) histories and contemporary politics. The complex cultural, religious and political issues that motivated 9/11 (and which have escalated in recent years) are similarly raised by Bennett’s inclusion of the text ‘In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful’, which swirls flame-like above the city’s skyline in these paintings, and is uttered by Muslims before any good deed. Yet as Greg Dimitriadis and Cameron McCarthy have noted, the use of this text by the artist further compounds the issues that are raised but not answered in these paintings, and is not without a certain irony: We are reminded here of the ideological disconnects which seem so much a part of our contemporary moment. The underside of a dynamically interdependent world is our profound sense of loss of control over ancestral markers of place and origins and a contingent struggle for meaning, identity, and affiliation. Indeed, while global flows of people, images, and technologies have drawn together heretofore far flung parts of the globe, difference has multiplied and intensified in stark and unforgiving ways. One person’s good deed is also the next person’s atrocity today. There differences are scripted across these paintings, as they are now scripted across the landscape of Manhattan.[90]

§

As the group of works that close this exhibition attest, Gordon Bennett’s recent body of abstract painting seems to almost sever itself from the work of the artist’s earlier career. Physically and emotionally exhausted by his postcolonial project, [91] Bennett sought a form of release. This was not an escape from content but a means of stepping away from the overwhelming power of figurative imagery, and the frameworks through which both the artist and his work have been contained and perceived throughout his career. While the obvious painterly quality of the surface of these works reveals Bennett’s ‘hand’ in a way not witnessed since his early student work, the artist is (quite deliberately) everywhere and nowhere in these paintings. This denial of information – in effect a refusal to ‘communicate’ [92] – also extends to the titling of these works, which are numbered in the sequence in which they are made in order to further discourage narrative connection and association.

Bennett’s abstract paintings may present a brave ‘front’ of ‘emptiness’ and reveal the artist’s obvious delight in the materiality of paint and juxtaposition of colour, but like all of his oeuvre, these works both bounce off and connect with precedents drawn from the history of Australian and international art. [93] So while Bennett may have attempted, in recent years, to disconnect from the politics of his earlier practice, there is also a sense within these paintings, of the impossibility of such a task. For given the artist’s own history of ‘engagement’, these works are not considered ‘simple’ abstract paintings, but abstract paintings by ‘Gordon Bennett’; coloured, or even tainted by, the history, concerns and associations of the artist’s earlier work. Yet embedded within this new and rapidly expanding body of abstraction is a sense of commitment and quiet determination – a willingness to both persist and push through these very issues. These beautiful and meditative paintings provide a space for contemplation for artist and audience and signal new directions. And we wait with anticipation to see just what those directions will be.

Text © 2007, National Gallery of Victoria. Image © Estate of Gordon Bennett. Reproduced with thanks.

Gordon Bennett is represented by Sutton Gallery, Melbourne and Milani Gallery, Brisbane

Notes

1 Gordon Bennett, ‘The manifest toe’ in Ian McLean & Gordon Bennett, The art of Gordon Bennett, Craftsman House, Roseville East, 1996, pp. 10–12.

2 Prior to attending art school Bennett trained as a fitter and turner and also worked as a linesman for the Australian Telecommunications Commission (now Telstra).

3 ‘… a lifetime in a secure though thankless job – later 3 years in an office with nothing better to look forward to.’ Gordon Bennett, unpublished notes, 1987. Collection of the artist.

4 As the artist explained to Anne Kirker during an interview in 1990: ‘I’ve always read all over the place. Before I went to college I was following theoretical texts as well as science fiction and fantasy novels, but most of the analytical texts I was reading had to do with psychology. As well as this I was in analysis and doing workshops in rebirthing, gestault theory etc …’ Anne Kirker, ‘Gordon Bennett: Expressions of constructed identity’, Artlink, vol. 10, nos. 1 & 2, Autumn/Winter 1990, p. 93.

5 Gordon Bennett, Australian icons: Notes on perception, unpublished, 1989. Collection of the artist. As Bennett has written: ‘I can’t remember exactly when it dawned on me that I had an Aboriginal heritage. I generally say that it was around age eleven, but this was my age when my family returned to Queensland where Aboriginal people were far more visible. I was certainly aware of it by the time I was sixteen years old after having been in the workforce for twelve months. It was upon entering the workforce that I really learnt how low the general opinion of Aboriginal people was. As a shy and inarticulate teenager my response to these derogatory opinions was silence, self-loathing and denial of my heritage.’ Gordon Bennett, ‘The manifest toe’, p. 20.

6 Bob Lingard, ‘A kind of history painting’, Tension, no. 17, August 1989, p. 41.

7 Susan Lowish, ‘Gordon Bennett: reading pictures’ in Lynne Seear & Julie Ewington (eds), Brought to light II: contemporary Australian art 1966–2006, Queensland Art Gallery Publishing, Brisbane, 2007, p. 185.

8 Terry Smith, ‘Australia’s anxiety’ in History and memory in the art of Gordon Bennett (exh. cat.), Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter, Oslo, Norway and Ikon Gallery Glasgow, Scotland, 1999, p. 10.

9 Gordon Bennett, ‘Aesthetics and Iconography: An artist’s approach’ in Aratjara: Art of the first Australians (exh. cat.), Kunstsammlung Nordrein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, Germany, 1993, p. 85.

10 The Royal Commission into Black Deaths in Custody was announced on 10 August 1987 by the then Prime Minister, the Honourable R. J. L. Hawke. It ran until 1991. See the National Archives Research Guide by Peter Nagle and Richard Summerrell, Aboriginal deaths in custody: The Royal Commission and its records, 1987–91 at http://www.naa.gov.au/Publications/research_guides/pdf/black_deaths.pdf [link no longer exists]

11 Gordon Bennett, Home sweet home, 1994, from the Home sweet home series, watercolour and pencil on paper.

12 Ian McLean, ‘Philosophy and painting: Gordon Bennett’s critical aesthetic’ in Ian McLean & Gordon Bennett, The art of Gordon Bennett, p. 74. For McLean’s in-depth discussion of this work see pp. 73–77.

13 Gordon Bennett, artist statement in Balance 1990: Views, visions, influences (exh. cat.), Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery, 1990, p. 46.

14 As the artist has commented: ‘It was natural for me to paint that way, given the anger I harboured … I read something about theories of the grotesque, and there’s a quote I have always kept – ‘The characteristic themes of the grotesque, The Temptation of St Anthony and The Apocalypse, to name a few, jeopardise or shatter our conventions by opening up into vertiginous new perspectives characterised by the destruction of logic and regression to the unconscious – madness, hysteria or nightmare. For an object to be grotesque it must arouse three responses. Laughter and astonishment are two; either disgust or horror is the third.’ I feel that by breaking a frame of reference, by introducing the novel or unexpected, the spectator may be jolted out of accustomed ways of perceiving the world …’ Anne Kirker, ‘Gordon Bennett: Expressions of constructed identity’, p. 93.

15 Thomas Keneally, The chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, Sydney, Angus & Robertson, 1972, and Fred Schepisi (dir.), The chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, 1978. Through their various critical commendations both versions of this story of a conflicted Aboriginal man caught between two cultures, brought the race relations of Australia’s colonial history to a wider audience. Kenneally’s novel was nominated for the Booker Prize in 1972 and Schepisi’s film received three AFI Awards in 1978 and was nominated for a further nine. It was also nominated for the Palm d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival that same year. Gordon Bennett also produced a painting titled The chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, 1988.

16 Gordon Bennett, unpublished notes on Outsider, March 1988. Collection of the artist.

17 As Bennett discussed with Chris McAuliffe during a 1993 interview: ‘Part of the reason I’m using projectors too is to remove myself to the point at which I become like a printing press. I’m not painting what I feel, I’m tracing it on the surface of the thing.’ Chris McAuliffe, ‘Interview with Gordon Bennett’ in Rex Butler (ed.), What is appropriation?: An anthology of critical writings on Australian art in the 80s and 90s, Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane and Power Publications, Sydney, 1996, p. 275.

18 Gordon Bennett, unpublished notes on Untitled, 1989, not dated. Collection of the artist.

19 Ian McLean, ‘Philosophy and painting: Gordon Bennett’s critical aesthetic’ in Ian McLean & Gordon Bennett, The art of Gordon Bennett, p. 89. Russian artist Kazimir Malevich (1878–1935) is one of the most influential abstract artists of the twentieth century and his work, particularly his iconic Suprematist painting Black square, 1915 (collection of The State Russian Museum, St Petersburg), has been of ongoing interest to Gordon Bennett.

20 ‘The images I select exist between the pages of art books and history books. Their unifying factor is the dot screen of their photo-mechanical reproduction and their iconographical relationships as points of reference on the Western cultural perceptual grid …’ Gordon Bennett as quoted in the preface of History and memory in the art of Gordon Bennett (exh. cat.), Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter, Oslo, Norway and Ikon Gallery, Glasgow, Scotland, 1999, p. 8.

21 For an in-depth discussion of this work see Susan Lowish, ‘Gordon Bennett: reading pictures’ pp. 185–91.

22 Crusoe Kuningbal, Kuninjku, c. 1922–86.

23 As Bennett attempted to explain at the time: ‘I won’t be appropriating any more Aboriginal images because I now more fully understand the situation. You have to understand my position of having no designs or images or stories on which to draw to assert my Aboriginality. In just three generations that heritage has been lost to me …’ Bob Lingard, ‘A kind of history painting’, p. 42. Gordon Bennett travelled to Maningrida in June 1989 to apologise for his actions. For further discussion of this issue also see Ian McLean, ‘Philosophy and painting: Gordon Bennett’s critical aesthetic’ in Ian McLean & Gordon Bennett, The art of Gordon Bennett, pp. 93–94.

24 Many of these images are based on the nineteenth century photographs of J. W. Lindt (1845–1926) [not identified as such by Bennett] which the artist sourced from photographic postcards. Gordon Bennett, unpublished notes on Australian icons: Notes on perception, 1989. Collection of the artist.

25 Gordon Bennett, ‘The manifest toe’, p. 41.

26 Gordon Bennett, ‘The manifest toe’, p. 43. Bennett’s footnotes within this text are: (1) Peter Sutton, Dreamings: The art of Aboriginal Australia (exh. cat.), Ringwood: Penguin Books, 1988, p. 18 and (2) ‘The term “psychotopographical” I found in a text that I have since been unable to relocate. It was referred to as a now “discredited” concept which to me seemed to be a perfect irony. It felt right to use this “discredited” term as a title for paintings that were exploring a Eurocentric perspective.’ See footnotes for Ian McLean & Gordon Bennett, The Art of Gordon Bennett, p. 123.

27 The Moët & Chandon Australian Art Fellowship was a prestigious art prize that recognised the achievements of young Australian artists up to the age of 35 years. The prize included $50,000 and a 12 month studio residency in Hautvilliers, France.

28 The primary image of The nine ricochets is taken from the woodblock frontispiece to AJ Vogan’s book The black police 1890 and is titled Queensland squatters dispersing aborigines. It is also reproduced in Bruce Elder’s Blood on the wattle, 1988, which was Gordon Bennett’s source. Bennett’s cropping of this found image is central to its interpretation. As Terry Smith writes: ‘Bennett has not used the section of the image which shows an Aboriginal woman, surrounded by the dead bodies of the men of the tribe, pleading for her life and that of her child, while a white squatter reaches for another bullet and a black policeman raises an axe. In The Nine Ricochets we see the axe itself raised, the hand obliterating the head of one Aboriginal man, while below a body is decapitated by the lower edge of the picture. Behind a man – white, Aboriginal? – leads off a young woman. Although no violence is directly shown, bloody murder and violation pervades the scene.’ Terry Smith, ‘Australia’s anxiety’, pp. 13–14. See this piece for an in-depth discussion of The nine ricochets (Fall down black fella, jump up white fella) as well as Rex Butler’s ‘Two readings of Gordon Bennett’s The nine ricochets’, Eyeline, no. 19, Winter/Spring 1992, pp. 18–23.

29 Tillers also quoted the work of both artists in his design for Sydney’s Federation Pavilion, which opened in 1988. Given the level of discussion around The nine shots, it is interesting to note, as Deborah Hart does, that it was displayed for the first time in Australia in 1988, three years after its execution. While it had been reproduced in the catalogue for the 1986 Sydney Biennale, it was not exhibited. It was first displayed in 1988 in the exhibition A Changing Relationship: Aboriginal themes in Australian art 1938-1988 at the SH Irvin Gallery, Sydney. Interestingly, it was later included in the exhibition Balance 1990: Views, visions, influences, at the Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, in which Gordon Bennett also participated. Deborah Hart, ‘Introduction: A work in progress’ in Deborah Hart (ed.), Imants Tillers: One world, many visions, Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 2006, pp. 12–13. It is important to note that Imants Tillers has since gone on to make collaborative works with Michael Nelson Tjakamarra.

30 Terry Smith, ‘Australia’s anxiety’, pp. 13.

31 Ian McLean, ‘The art of Gordon Bennett’ in Ian McLean & Gordon Bennett, The art of Gordon Bennett, p. 94.

32 Gordon Bennett and Imants Tillers were also invited to collaborate on the exhibition, Commitments, which was held at the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane in 1993. Bennett exhibited the faxed correspondence between himself and Tillers that occurred in the lead-up to the exhibition along with an adaptation of Tillers’ stacked canvas board work and his own versions of Tillers’ de Chirico-inspired painting, which drew upon the artist’s Greetings of a distant friend of 1916. Bennett has since lost the fax correspondence from this project. For a brief discussion of the ‘dialogue’ between Bennett and Tillers see, Deborah Hart, ‘Introduction: A work in progress’, pp. 12–13. For Imants Tillers’ account of this exhibition see Imants Tillers, ‘Poetic justice: A case study (Due allocation of reward for virtue and punishment for vice)’, Midwest, no. 5, 1994, pp. 10–15.

33 Ian McLean, ‘Towards an Australian postcolonial art’ in Ian McLean & Gordon Bennett, The Art of Gordon Bennett, p. 103.

34 Bennett has also said that these evoke ‘the scars on black peoples’ memory’. Gordon Bennett, ‘On four paintings produced in France’, unpublished notes, 3 July 1992. Collection of the artist.

35 Ian McLean, ‘Towards an Australian postcolonial art’, p. 103.

36 The figure of Pollock himself (sourced from the well-known body of photographs by Hans Namuth of the artist painting) appears in Gordon Bennett’s later Notes to Basquiat: Modern art series of 2001.

37 As Bennett has stated: ‘The painting is as much whipped into being as it is “danced” into being, ie. the “ritual” act of painting.’ Gordon Bennett, ‘On Four Paintings Produced in France’.

38 Ian McLean, ‘Conspiracy theory: Pollock, Basquiat, Bennett’ in Gordon Bennett. Notes to Basquiat: Modern art (exh. cat.), Sherman Galleries, Sydney, 17 May–9 June 2001, n.p.